In 1701, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) broke out in Europe. It was triggered by the death of childless Charles II of Spain, leading the French Bourbons and the Austrian Habsburgs to begin fighting over the Spanish Empire.

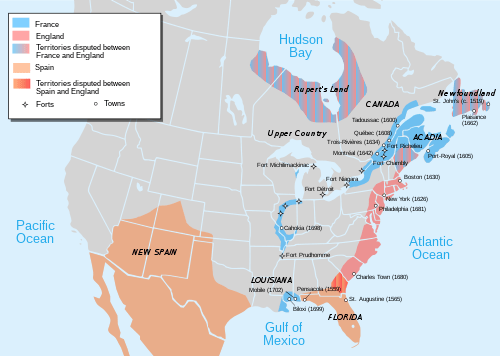

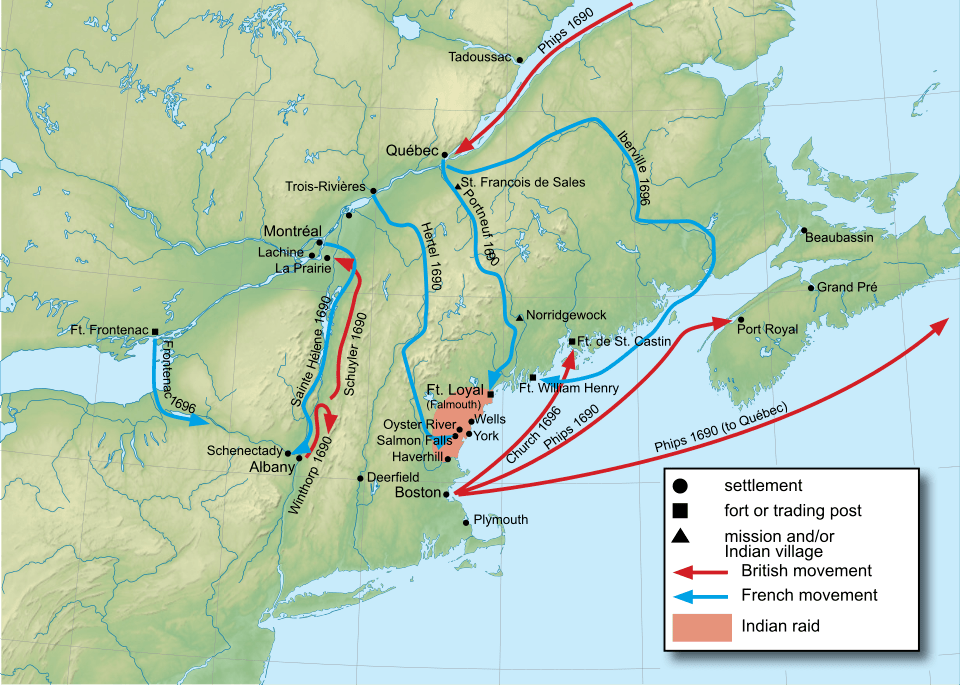

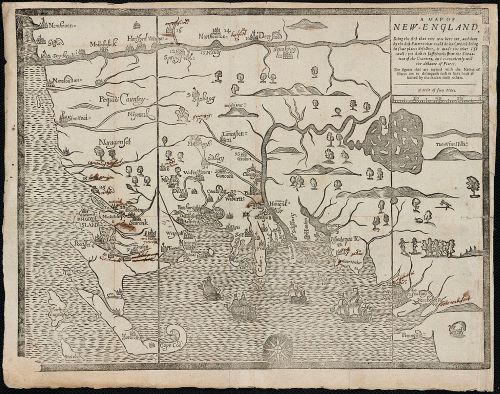

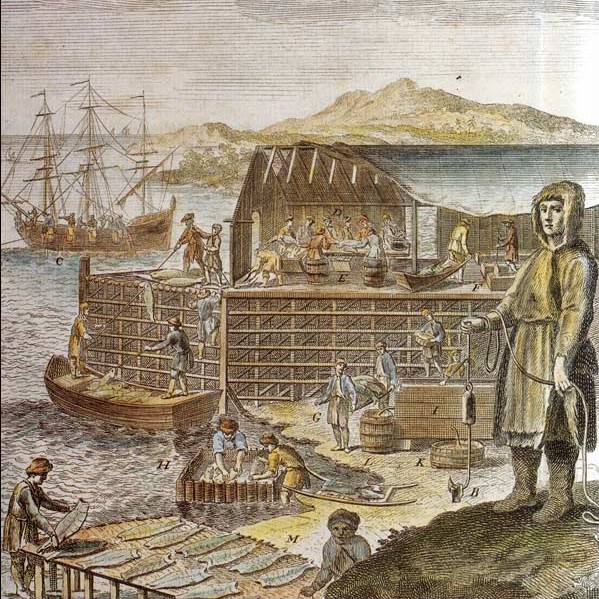

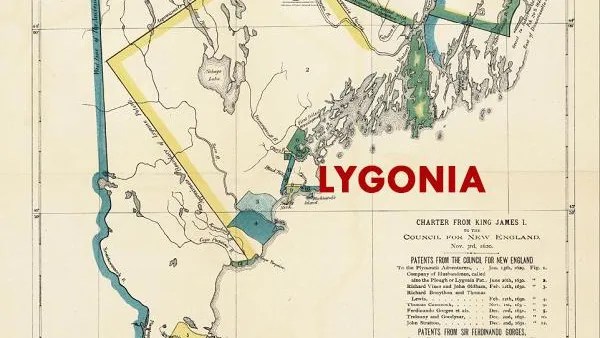

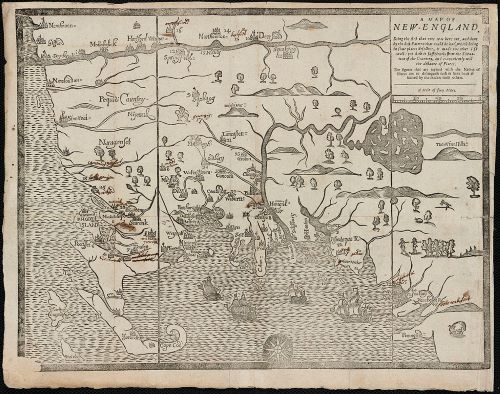

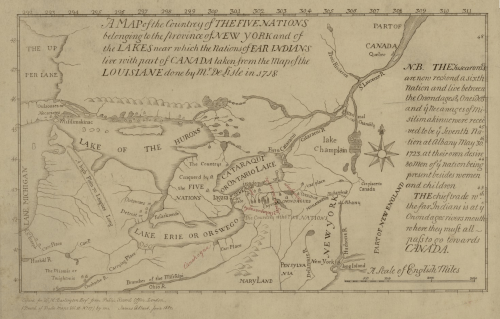

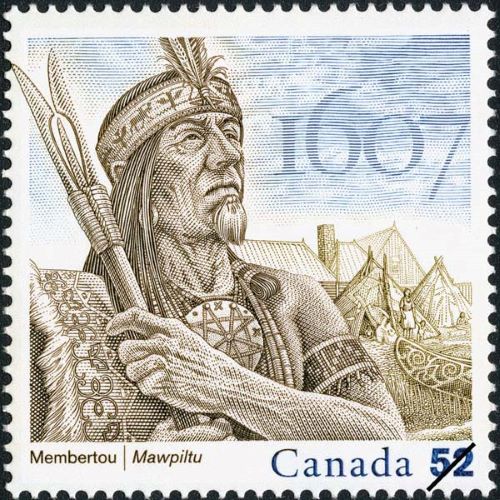

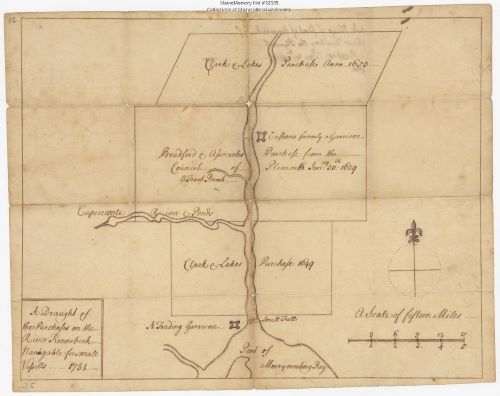

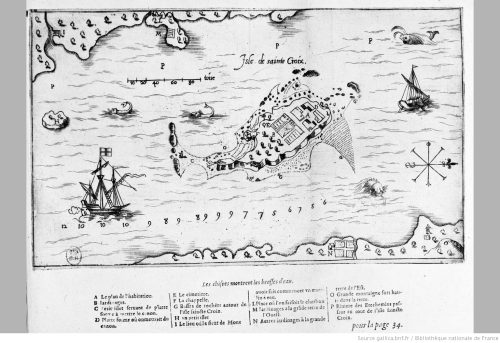

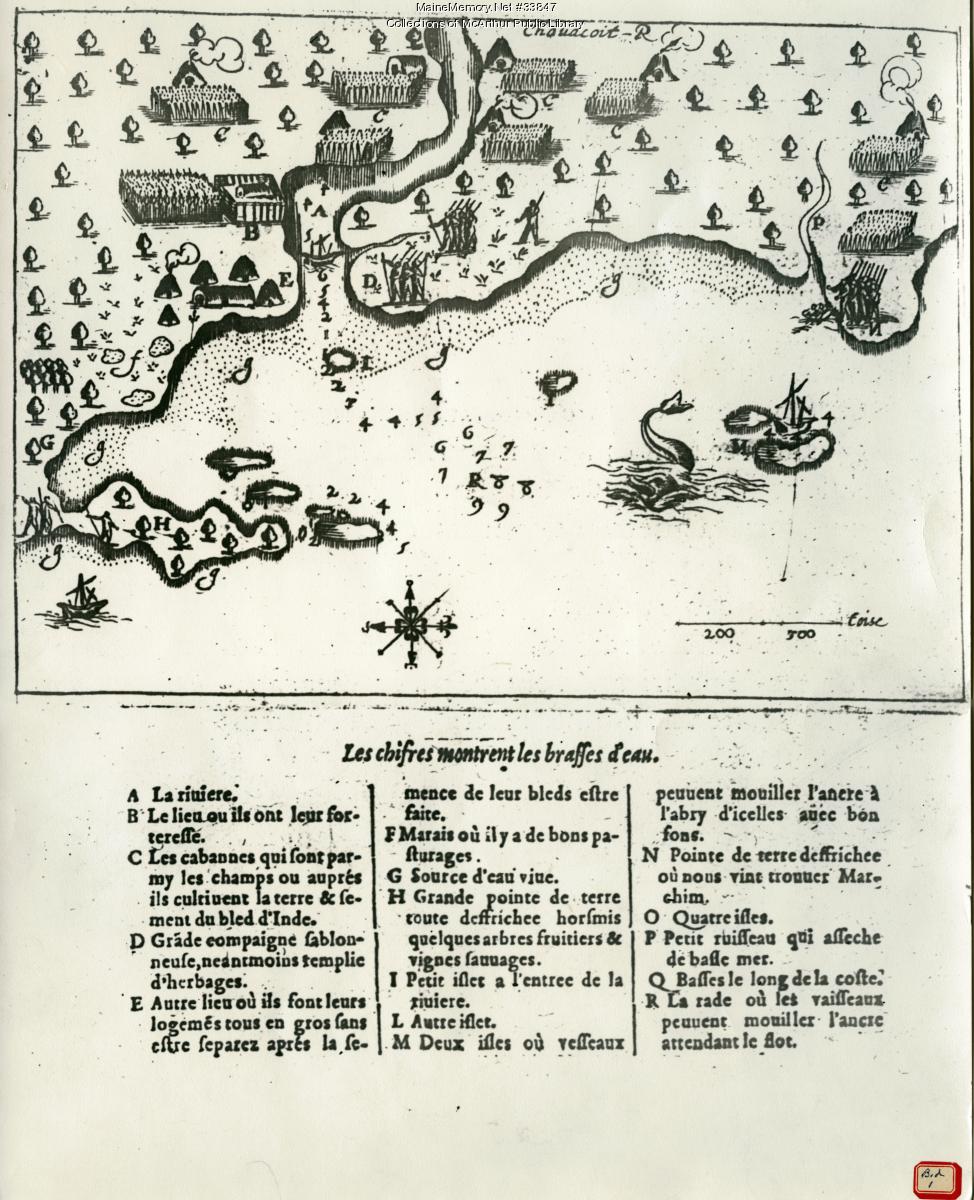

The War of the Spanish Succession spilled over into North America, where it was known as Queen Anne’s War, and involved the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain. It was battled with Indigenous allies on three fronts: 1) Spanish Florida and the English Province of Carolina, 2) English St. John’s and Newfoundland, and the French at present-day Placentia, and 3) French Acadia with English New England on the Maine frontier.

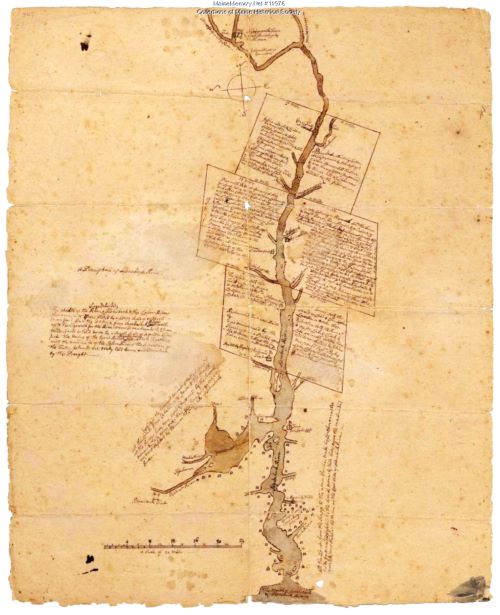

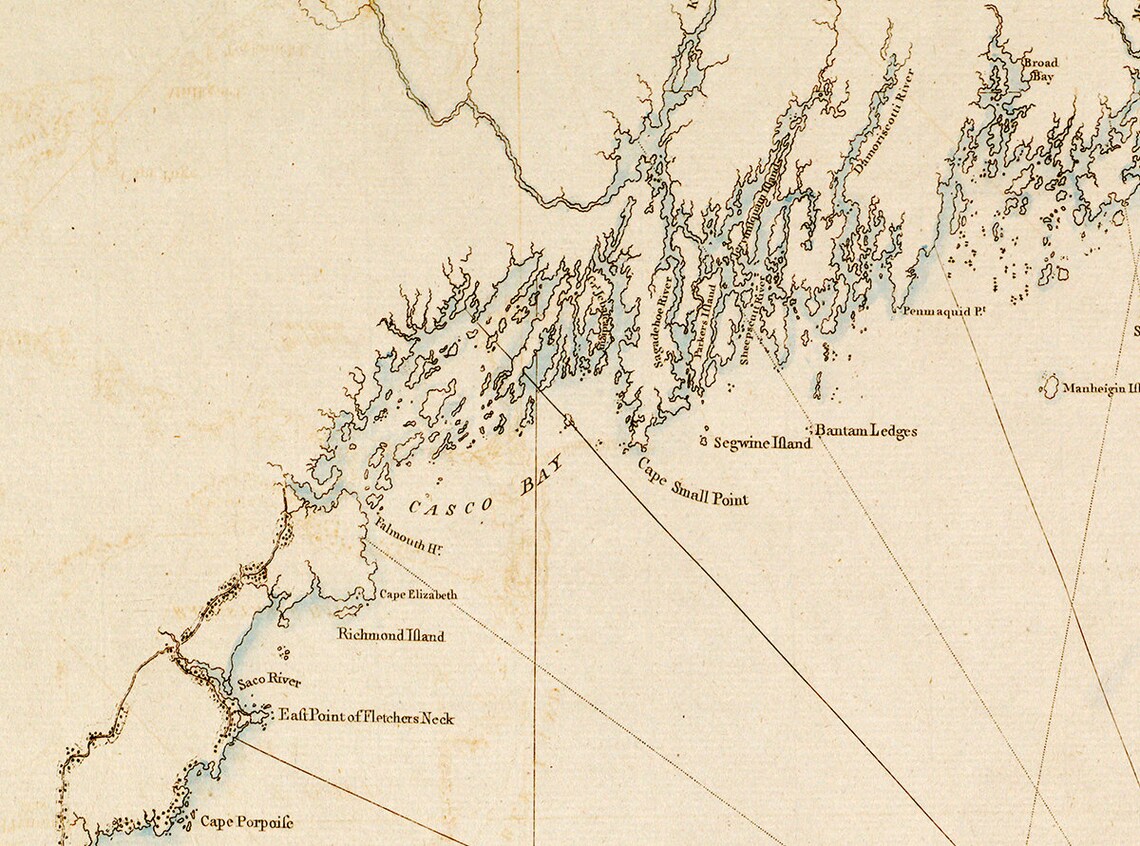

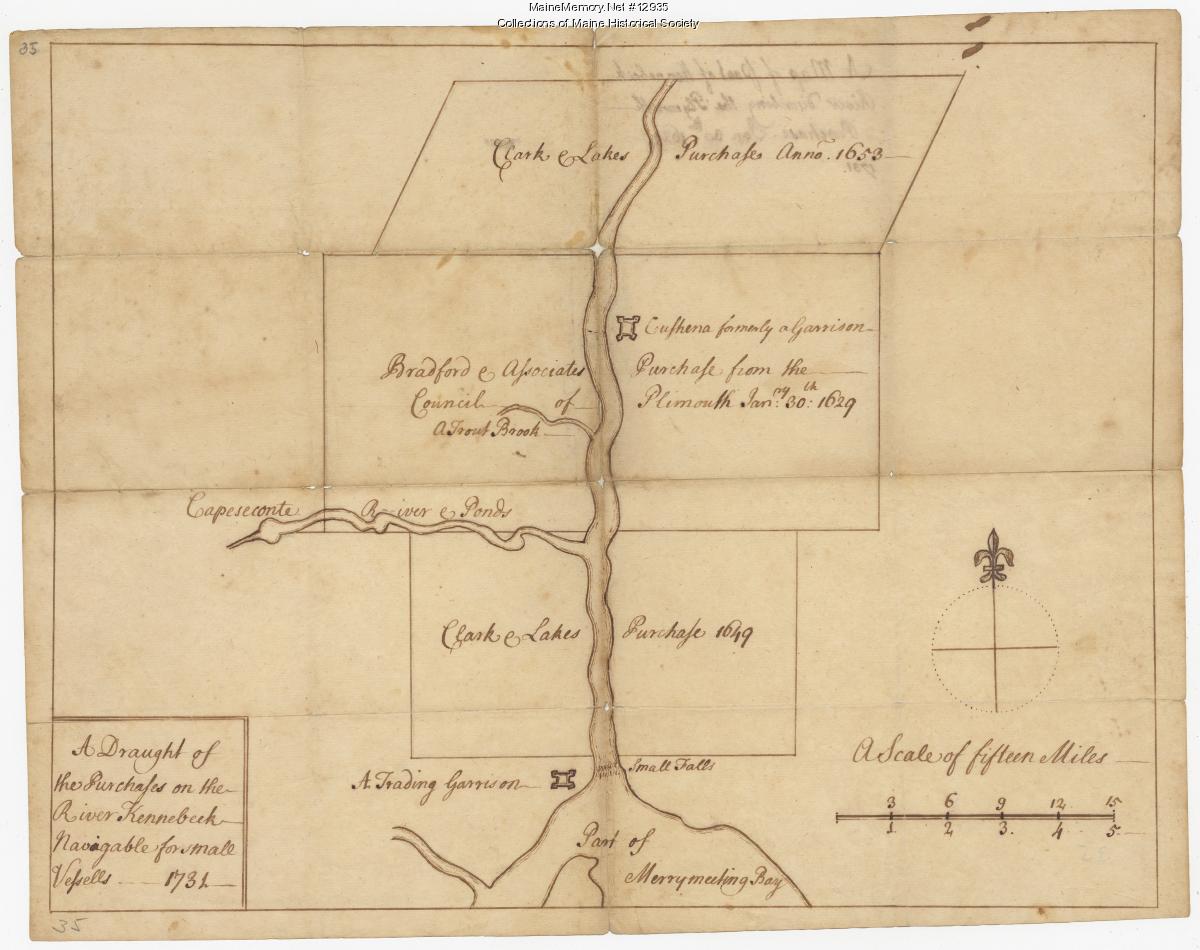

On August 6, 1703, the War began in Maine when the Royal Governor of New France, Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil, sent an expedition force of 500 French and Mi’kmaq from the St. Lawrence River Valley to make a massive assault on all the English coastal towns and forts stretching from Wells to Falmouth.

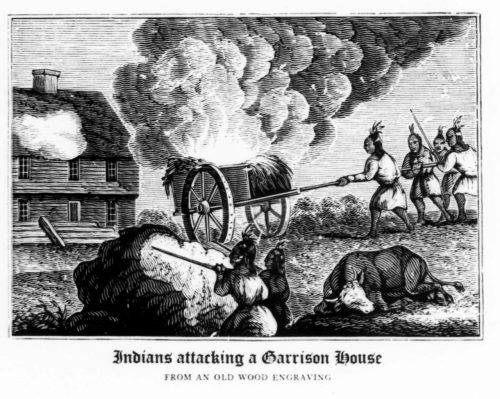

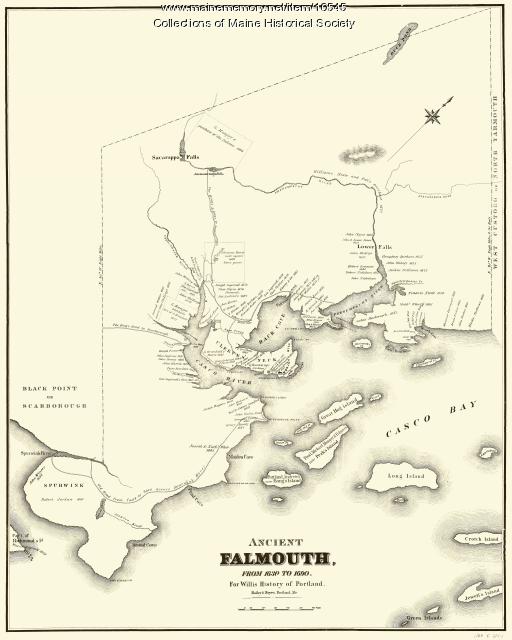

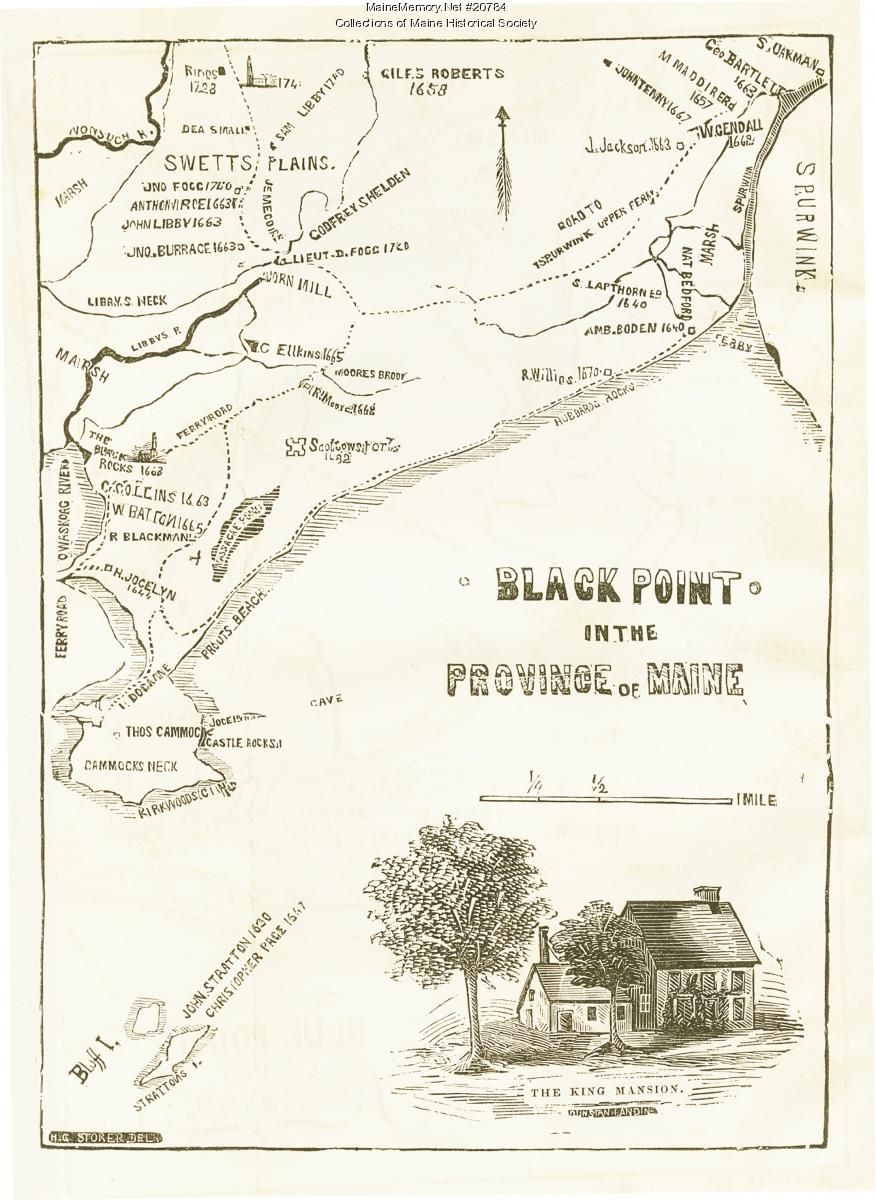

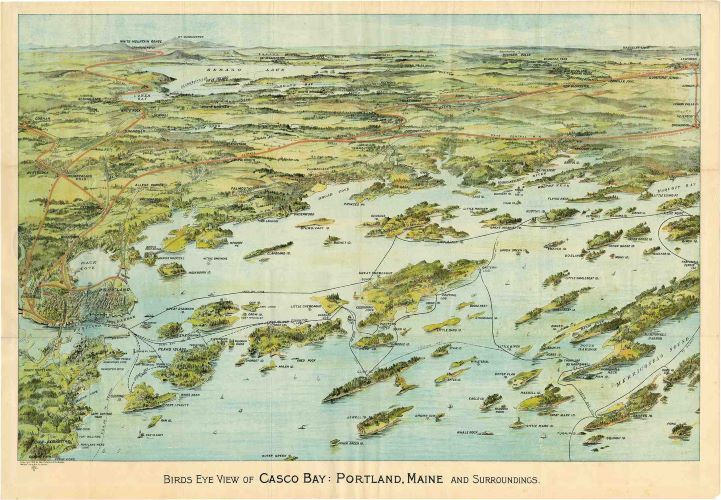

This expedition force laid coastal Maine to waste once again. As described by Willis (1833, pp. 7-8): “The inhabitants of Purpooduck [near Cape Elizabeth] were the most severe sufferers in this sudden onset. There were nine families then settled upon and near the point who were not protected by any garrison. The Indians came suddenly upon the defenseless hamlet when the men were absent, killed 25 persons, and took several prisoners. Among the killed were Thomas Lovitt and his family, Joel Madeford or Madiver, and the wives of Josiah and Benjamin Wallis and Michael Webber. The wife of Joseph Wallis was taken captive; Josiah Wallis made his escape to Black Point with his son John, then 7 years old, part of the way upon his back.

Spurwink, principally occupied by the Jordan family, was attacked at the same time, and twenty-two persons by the name of Jordan were killed and taken prisoners. Dominicus Jordan, the third son of the Rev. Robert, was among the killed, and his family, consisting of six children, was carried to Canada. His brother Jeremiah was among the prisoners, who was subsequently called French Jeremy, from the circumstance of his having been carried to France.

The whole country, from Purpooduck Point to Spurwink, was covered with woods, except the few spots which the inhabitants had cleared. This afforded facilities to the Indians for concealment and protection. From these coverts, they made their sudden and cruel visits, then returned to mingle again with the other wild tenants of the forest, beyond the reach of pursuit.”

At this point, only the fort and settlement at Falmouth remained. “This was the most considerable fort on the eastern coast and was the central point of defense for all the settlements upon Casco Bay; under its protection, several persons had collected to revive the fortunes of the town” (Willis, 1833, p. 8). The veteran Major John March was in command of the fort.

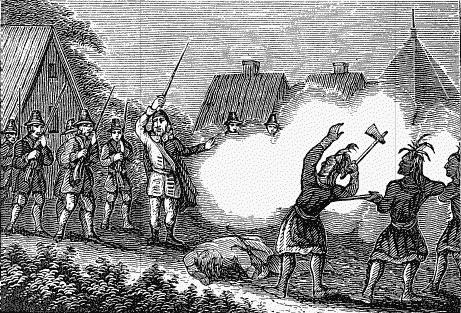

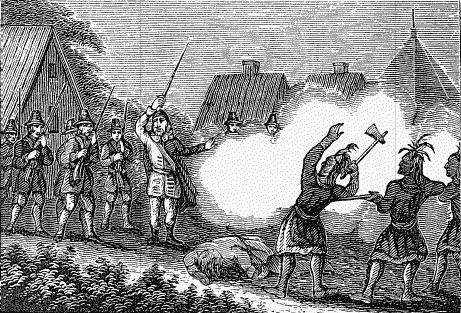

The assault began by deception and treachery (Drake, 1910, pp. 159-160): “While the main body of assailants was kept out of sight, three chiefs boldly advanced to the gate with a flag of truce. At first, March paid no attention to the flag bearers but finally went out to meet it, taking with him two others, all three being unarmed. His men were, however, warned to be watchful against treachery. Only a few words had been exchanged when the Indians drew their hatchets from under their blankets and fell with fury upon March and his companions. Being a man of great physical strength, March wrested a hatchet from one of his assailants, with which he kept them at bay until a file of men came to his rescue. Luckily, he escaped with a few slight wounds …

Having failed to gain the fort by treachery, the savages next fell upon the scattered cabins outside, which were soon blazing on all sides. After this was done, they returned to attack the fort. For six days, the weak garrison defended itself unflinchingly. During this time, the besiegers were joined by the confederate bands, Falmouth holds, who had been destroying all before them out at the west. Beaubassin, the French leader, now pressed the siege with greater vigor and skill. Covered by the bank on which the fort stood, the savages set to work undermining it on the waterside. For two days and nights, they steadily wormed their way under the bank toward the palisade without any hindrance from the garrison and were in a fair way to have carried the fort by assault when the arrival of the provincial galley compelled them to give over their purpose in a hurry, as that vessel’s guns raked their working party. On the following night, they decamped. Two hundred canoes were destroyed, and an English shallop retaken by the relieving galley.”

One hundred and thirty persons were either killed or taken captive during this bloody conquest. Fear and dismay now filled the hearts of the settlers, for Maine had come very close to receiving a death blow. Only the strongest-willed remained, hunkered down in their garrisons, performing only the most necessary outside labor under armed guard.

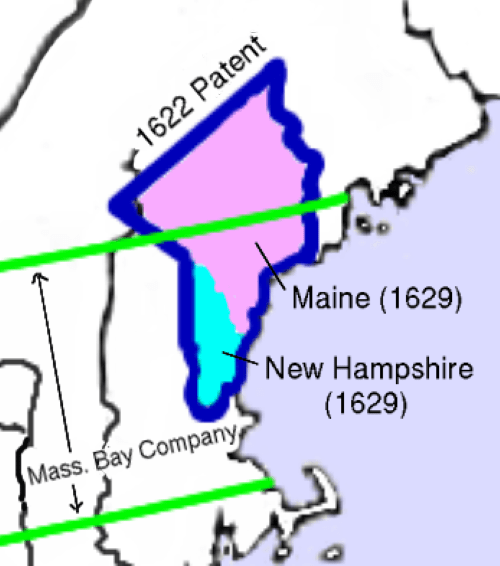

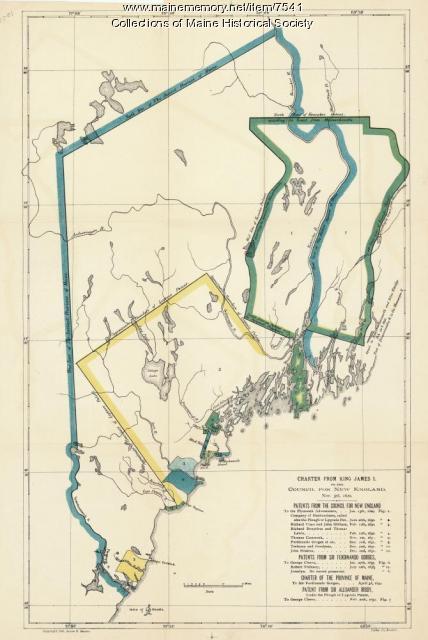

Illustration: European occupation of North America at the start of Queen Anne’s War. Wikimedia

Bibliography

Drake, S. A. (1887). The Border Wars of New England, commonly called King Williams and Queen Anne’s Wars. Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York.

Willis, W. (1865) The history of Portland from 1632 to 1864. Bailey and Noyes: Portland.